“We don’t have guns and rifles, but we have truth in our voices.”

“And you will know the truth, and the truth will set you free.”

John 8:32

I was part of the interfaith learning tour to the Philippines organized by the International Coalition for Human Rights in the Philippines and the National Council of Churches in the Philippines (NCCP), a United Church Mission and Service partner in the Philippines, in March 2023. “Interfaith learning tour” sounds touristy, but the situation in the communities we met with resembled more of an ongoing war than a tour.

Our team of faith and community organizers from the United States and Canada went with enthusiasm and excitement to Cagayan Valley province, a 10-hour bus ride from the capital, Manila. After a quick briefing from the local organizers, we interviewed folks from militarized communities. Our excitement and enthusiasm immediately faded when we entered the room of people whose eyes were filled with grief and terror. Our local coordinators told us that they were “red-tagged.” Red-tagging or red-baiting is the act of labelling individuals and groups as communist fronts, which legitimizes the violence done to them by the state. Red-tagging sets into motion the potential for violence—arrests, beatings, extrajudicial killings—that the military would inflict on these communities.

Josa, not her real name, came to tell us how her husband, a leader in the local farming community, was brought to the military barracks to force him to surrender for a crime he knew nothing about. She was on the brink of crying as she told us how the soldiers hurt her husband. She remembers his shrieks and the agony on his face. Many in their communities were forced to surrender for fabricated crimes. All they know is that they lobbied for better government services during the pandemic, but they were charged as communists. When the military set up camp in the barrio (village) in 2020, a climate of fear gripped the community. One of the women said, “Before they came we would go to our field until 6 p.m., but since they came we only stay until 3 p.m., definitely before sundown.” The farmers are scared. They feel that every movement they make is watched. Their crop production has decreased, and the military has stolen their crops and killed their farm animals. When these men are confronted, they respond as if they know nothing about what happened.

Ate Nelia and her husband, esteemed community leaders, have also been red-tagged. One night, a group of armed men forcibly entered their house. They had no court documents to justify their entry, but the whole family was thrown out and her husband was arrested. The memory of her youngest daughter crying still pains Ate as she recounts that night. She was allowed to enter their home after several hours but was surprised to see grenades and high-calibre guns spread out in their living room, weapons she would never allow into their house. It’s been well-documented that the military often plants evidence to persecute civilians, a similar strategy they used in their “war on drugs.” Ate’s husband is still imprisoned at this time.

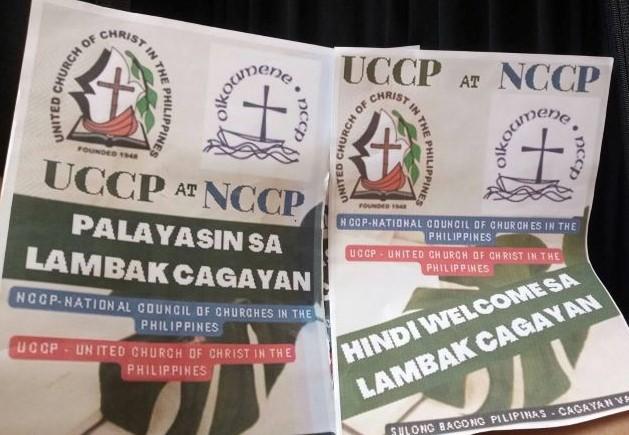

I did not expect that we, folks coming from outside the Philippines, would be red-tagged. We planned to visit a priest in the community in what we imagined would be a time of fellowship and prayer, but that did not happen. A day before we were set to go, posters were distributed in the community saying that the NCCP and United Church of Christ in the Philippines (UCCP) were not welcome in Cagayan Valley. The local organizers decided to err on the side of caution and cancel our visit based on many cases of harassment and violence that were preceded by such posters. None of us expected to experience red-tagging first hand, and it was very distressing. The people we interviewed possess the truth of their suffering, and that truth challenges the government’s justification for militarization. Hearing their stories and experiencing red-tagging, I am confronted with a spiritual and moral decision to heed the voices of suffering over the mighty logic of power that the military exploits. The pain, the narrative of violence, will remain in my body. I hope I can use this pain to help campaign to restore civilian order of communities that are under heavy militarization and to free political prisoners in the Philippines.

Although the people we interviewed exhibited emotional exhaustion, they also exuded hope and a strong resolved to continue the fight until they live a life without a shadow of military establishment in their community. The words of Josa ring in my ears, “We don’t have guns and rifles, but we have truth in our voices.”

—Ariel Siagan is a United Church member who participated in an Interfaith Learning Tour organized by Mission and Service partners the National Council of Churches in the Philippines and the International Coalition for Human Rights in the Philippines.

Interested in participating in a people-to-people opportunity with a global partner? We invite you to find out more on the People in Partnership webpage or by e-mailing .

The views contained within these blogs are personal and do not necessarily reflect those of The United Church of Canada.