For the International Day for the Abolition of Slavery, Peter Cruchley writes about the Council for World Mission’s efforts to seek truth and make reparations for its historic role in support of slavery.

I have worked for Council for World Mission (CWM) since 2016 when I joined to become the Mission Secretary for Mission Development. But, in fact, my life and work has oddly been shaped by CWM as I was born to missionary parents living and working in Zambia, central eastern Africa. They had gone in 1959 prior to independence and during that time my father had been threatened with arrest because of his support for independence. This commitment to decolonization shaped my parents’ vision of mission and so it has with mine as I work within an organization committed to mission in the context of empire.

The Council for World Mission came into being in 1977 to dismantle the old order of empire, when the London Missionary Society (LMS) sent missionaries to its churches around the world and decided from London what were the mission priorities of the Pacific, Asia, Africa, and the Caribbean. (This was the mission organization which sent my parents to Zambia.) But empire remains deeply rooted in the realities of our world today. Political and economic power continues to amass to itself the wealth of the earth just as it did during the era of European empires. Thus, CWM is committed to the work of decolonization still, especially in the work we do on economic justice, in which we see how empire has reestablished itself in the new structures of capitalism and White power.

Manifestations of empire continue in CWM’s life as we have discovered all too painfully in our program on the legacies of slavery. I led a series of hearings through 2017-2018 where we gathered to discern the legacies of slavery in the past of London Missionary Society and how the inheritances of racism, economic inequality, and generational trauma feature still in our shared life together as a partnership of churches, as well as in the communities we serve. In the testimonies of contemporary and historic witnesses the complicity of mission agencies and missionaries with racist and colonial power was laid bare.

In my research I discovered that two of the London Missionary Society treasurers, William Hankey and Sir Culling Eardley Smith, received significant sums in “compensation” for the emancipation of the enslaved Africans working on plantations they owned in Jamaica and St. Kitts. Hankey’s own plantation was eventually sold in 1954 and its proceeds paid into the accounts of CWM’s predecessors.

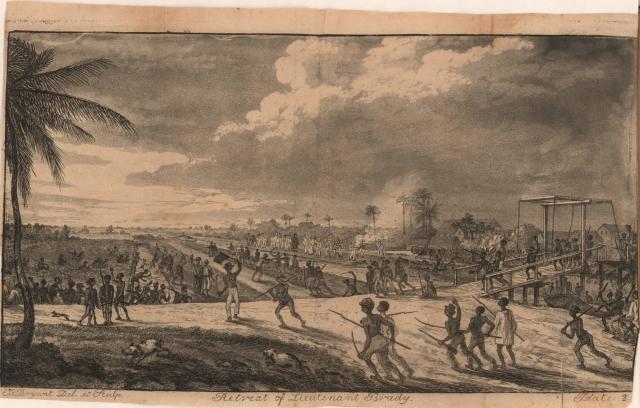

In the early 1800s, when confronted with the legitimate grievances of enslaved people in Guyana, the London Missionary Society instructed its missionaries to remain silent on the matter of emancipation. They wrote to the LMS missionary Rev. John Smith explicitly stating: “You are not sent to relieve them from their servile condition, but to afford them the consolation of religion.” Thus, when Quamina and the leaders of the Demerara revolt of 1823 came to Smith seeking advice he told them to stay at home and wait for their deliverance.

The LMS received its resources from the emerging British middle classes who were at the heart of the Industrial Revolution and the capitalism funding it. The LMS was deeply complicit in the White British colonial project and its enslaving practices. The celebrated LMS missionary, David Livingstone’s famous encapsulation of the missionary endeavor: “Christianity, commerce, and civilization” can be seen in all levels of the life of LMS. The London Missionary Society used slave ships to transport missionaries, paraded black people as spectacles on deputation visits, produced materials for children and adults on the superior calling and nature of White people and the inferior and sub-human nature of Black people, and remained silent on abolition until the eve of emancipation. Race is a colonial construction. Before the White European empires humanity was not delineated by “race.” It is clear the huge part missionaries had to play in teaching this new doctrine and especially the religiously and politically asserted superiority of White people and “civilization.”

The Council for World Mission hearings on the legacy of slavery added contemporary evidence of how churches and mission agencies remain complicit in supremacist visions of human beings and are silent in the face of Afrophobia, racism, and prejudice. They also offered an urgent call to repent, make reparation, and create change. And in this spirit CWM has responded in repentance and hope. The board of directors has committed CWM to a 10-year commitment to the work for racial justice and to invest significantly in Black communities. CWM will seek to raise up Black power and dignity, dismantle White privilege, create new forms of mission and evangelism which don’t do violence to others, and challenge others to see mission as restorative justice led by and in the interests of those exploited by colonialism and capitalism.

I hope if Quamina were to come to the leadership of Council for World Mission today to seek our solidarity in their struggle for freedom we would not tell him to stay at home and wait, but tell him we are on our way to join their uprising.

—Peter Cruchley, Mission Secretary for Mission Development at the Council for World Mission.