The thought process that underlies Trump's alleged statements about immigrants and the countries they come from is also very much present here in Canada.

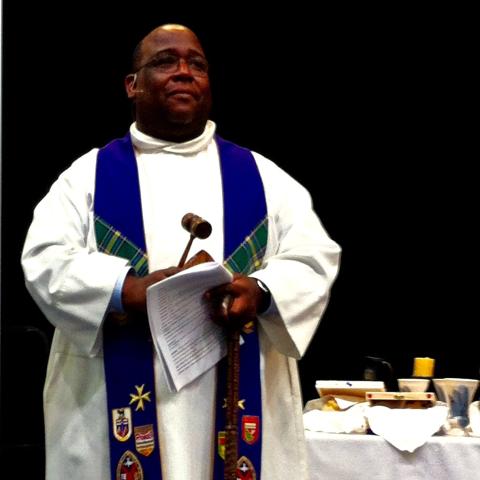

Full disclosure. I am a Black man. I was born in Jamaica and I am an immigrant to Canada. Having served as an ordained minister of The Methodist Church in the Caribbean and the Americas, I am now an ordained minister of The United Church of Canada. I wanted to say this upfront so that you can understand the context from which I speak. Let me be also very clear that when I speak about immigration I am speaking specifically and only about those persons who are lawful and legal immigrants to a country.

Like so many, I listened with concern and deep distress recently to the comments attributed to the President of the United States concerning Haiti and African nations. I have also listened also to the many surrogates and supporters of the President who have tried to explain away the alleged comments. Am I offended? Yes, I am! But to be honest, I was not surprised by the alleged statements made. If I distill away the vulgarity of the alleged statement, what is really of concern to me is the thinking and sentiments behind it. The specifics of the statement aside, I am more concerned about what it is being said about immigrants and especially those from predominantly Black countries. When I view the situation through those eyes I see that the thought process that underlie those alleged statements is also very much present here in Canada.

The decision to emigrate from one’s country to another country is never done lightly! For whatever the reason, when a person emigrates they come to a new country usually with the intention of working hard to make a better day for themselves and their families. They come seeking to stand on equal terms with those around them as they seek to eek out a living in their adoptive home. In many ways the immigrant and their children have come to know that they will have to work harder than the people who are born here for the same recognition. I know that I will always have to work harder than my Canadian counterparts if I am to be stand on equal footing with them in the eyes of many congregations and church members.

The data from both Canada and the U.S., however, points out that far from being indolent, lazy, and being a drain on the social services of the country, immigrants have, in the main, worked and studied hard to be productive members of the society. It is regrettable that there is too often a sense of condescension that greets immigrants and sees their skills as not as good as their counterparts in their adoptive country. In some cases, immigrants have attitudes directed at them attitudes which say they should accept whatever is thrown at them because “where they are coming from, things are not as good as here.”

One of the things I had to get accustomed to when I arrived in Canada was being constantly asked the question, “Why have you come here?” Initially I thought it was curiosity. However, after a while the questioning became tiresome and I began to wonder if there was something more to it than what I was hearing. Indeed, on one occasion someone had to remind an inquirer that “apart from the Indigenous people, all us in this country either immigrated or are the descendants of immigrants to Canada.”

I sat in a meeting in Alberta where ministers who came into the United Church from other denominations met. Some very interesting facts emerged from the discussions. The ministers from countries with predominantly White populations (e.g. U.S., Australia, countries in Europe) reported that they had made on average 5–10 applications to seek an initial appointment. However, ministers from predominantly Black countries (e.g. countries in the Caribbean or Africa) had made on average 30–80 applications to seek an initial appointment. Also, many Black ministers reported a tendency for people to believe there was a deficiency in their ministerial formation and that they needed to be further trained to do the job of ministry in Canada. I recall, for example, one kind-hearted member of my pastoral charge offering to assist me to construct sermons, and this was even before he heard me preach! I would have discounted my personal experiences as being isolated, however, when I hear it as being a normative experience of other Black immigrant ministers, then it gives me reason to pause. There is need for us to examine the inherent bias we may have toward people from the so-called lesser developed countries. While we speak the language of equity, sometimes we have allowed and excused some attitudes which contradict the very things we speak.

I have said elsewhere, that during 2017 the ideal of Canada being a multicultural nation came under tremendous pressure. There were far too many instances of racial and cultural intolerance occurring in our country. Unfortunately, those who are Muslim, or Black, or Indigenous have received the brunt of these vicious and unwelcomed attentions. The example of the killing of six worshippers while they were in prayer at the Islamic Cultural Centre of Quebec City stands as a testimony of this reality. The experience of the Black female minister of the United Church in Thunder Bay who had racial slurs hurled at her to the extent that she feared for her safety stands as testimony to this reality. The young Black man in Edmonton who was innocently going on his way to have someone shouting at him, “the n****rs are coming,” also stands as testimony of this reality. Should I go on? While we lift the official ideal of multiculturalism, the reality on the ground is that the sentiments, not necessarily the specific words, as allegedly expressed by the U.S. President may well be held by more people in Canada than we want to imagine.

At the same time, I am reminded that last year at a United Church, a speaker commented on a statement heard years before which suggested that the United Church needs to be careful about who they allow in as ministers. That person’s concern was that by allowing entry to the ministerial leadership of the church to those from a non-Canadian context we may well be in danger of losing our theological identity as a denomination. While the statements I heard were concerning to me, what was sad was the fact that, to date, I have heard no retraction, clarification, or explanation offered by officials at the pastoral charge where the event occurred. Allowed to stand without clarification, it can be interpreted that persons like myself are to be viewed with suspicion and that we are not to be fully accepted by the church. Indeed, it seems to be saying that ministers like myself are not the type that the church needs. How different really is the thinking expressed here from the thinking which underlie the alleged statements from the U.S. President?

I am not surprised by the words attributed to the U.S. President. If anything, I am saddened. Yes, I will stand in righteous indignation against the vulgarity of the alleged statement. I will also, however, speak out against the feelings of intolerance faced by legal immigrants of colour. This reminds me of just how much work the church must do to help our nation, and our world, realize that all persons are important, and all persons deserve respect. No person should be disparaged because of their colour, their race, religion, sexual orientation, country of origin or immigration status.

—Paul Douglas Walfall is the ministry personnel in the Fort Saskatchewan Pastoral Charge in the Yellowhead Presbytery, Alberta and Northwest Conference.