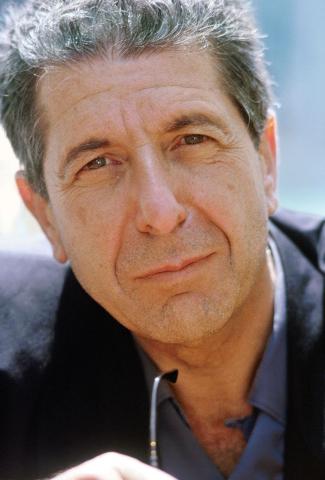

Leonard Cohen always acknowledged the pain and sadness of life; maybe that’s why he slid so deeply into our hearts.

I have had a long love affair with Leonard Cohen, or rather, with his words. I furiously read his poems in university; I saw him in concert in 1970, when he came to play in a small indoor hockey rink in Kingston, Ontario; I learned to play “Suzanne” on my guitar, and channelled Cohen’s angst-filled love. I was envious of his time in the Greek Islands, and was determined to do the same, even to the point of taking a year’s worth of evening classes in conversational Greek – but alas, my visit only lasted a couple of months. Just a couple of years ago my spouse got us tickets for Leonard’s final concert in Vancouver – we were in the tenth row from the front (my birthday gift for several years running), and I got to wave and weep. Leonard’s poetry kept showing up in my sermons; in benedictions –“Holy and shining with a great light, is every living thing, established in the world and covered with light, until your name is praised forever” ("43," Book of Mercy. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart Inc., 1984.); in my nomination speech as a candidate for Moderator in 2012 (and although I changed the pronouns, I think Cohen would have been okay with that):

If it be your will

That we speak no more,

And our voice be still

as it was before,

Then we will speak no more,

We shall abide until

We are spoken for.

If it be your will

That a voice be trueFrom this broken hill

We will sing to you

From this broken hill

All your praises they shall ring

If it be your will

To let us sing.

(“If It Be Your Will,” Various Positions, 1984, Columbia Records)

… these still feel like words the United Church needs to keep singing.

It was Leonard’s poetry that brought some hope to the sermon on November 13, when anguish about the election of Donald Trump to the presidency seemed to derail us, with a word from his second-to-last album, Popular Problems (“You Got Me Singing,” 2014, Columbia Records):

You got me singing,

Even though the news is bad,

You got me singing

The only song I ever had.You got me singing,

Even though it all went wrong,

You got me singing,

The hallelujah song.

… which then led into a soloist singing “Hallelujah,” and all of us humming along, weeping even as we softly joined in on the hallelujahs.

Cohen feels like the quintessential SBNR (spiritual but not religious) person: born and raised a Jew; who explored the wonder of sensuality, sex and love; who spent several years in a Buddhist monastery; who was endlessly inventive in using Christian imagery in his songs. Perhaps reflecting his Jewish heritage, Leonard never named God in his poetry, but an elusive “you” frequently points to the unnamed Mystery. And surely he must have revelled in the Bible’s “Song of Songs,” where the celebration of love with all its rootedness in the flesh, in the here-and-now, becomes a powerful metaphor for his passion for the Holy.

Cohen always acknowledged the pain and sadness of life; maybe that’s why he slid so deeply into our hearts. He struggled with depression, and he let it show in his writing. He wrote about hurt and loss and despair – “broken” was one of his favourite words. And yet he trusted in the mystery of grace: “Having lost my way, I make my way to you; having soiled my heart, I lift my heart to you; having wasted my days, I bring the heap to you… here is the opening in defeat.” ("41," Book of Mercy. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart Inc., 1984.)

For Cohen, the personal slides easily into the social and the political, from the ironic poignancy of “Democracy is coming to the U.S.A.” (“Democracy”); to the terror of “Get ready for the future: it is murder.” (“The Future”) He knows what we are capable of: “You want it darker – we kill the flame.” (“You Want It Darker”) But ultimately, Cohen never gives in to nihilism; he is, rather, a prophet calling for repentance.

For always, there is a hope that goes beyond the darkness, or the terror – the light that comes through the crack, the love that in the face of everything falling apart, still makes it “real;” the presence who “illuminates outrageous evil.”

And then there was the quiet laughter, the wry comment, the willingness to poke fun at himself – “a lazy bastard living in a suit”(“Going Home”); who is “…fighting with temptation [that] I didn’t want to win; a man like me don’t like to see temptation caving in”(“On the Level”); the one whose advice was “to laugh and cry and cry and laugh about it all again” (“So Long, Marianne”)

And maybe that’s what we need to do, laugh and cry and cry and laugh about it all again, as we remember Leonard Cohen… the man who sang through the pain and the laughter, embracing love and loneliness, giving us glimpses of the Mystery, helping all of us to sing,

For even though it all went wrong

I’ll stand before the Lord of Song

With nothing on my tongue

But hallelujah.

(“Hallelujah,” Various Positions, 1984, Columbia Records)

- Gary Paterson.

Gary Paterson is former Moderator of The United Church of Canada and ministry personnel at St. Andrew's-Wesley United Church in Vancouver.