Why do we get days off at Christmas?

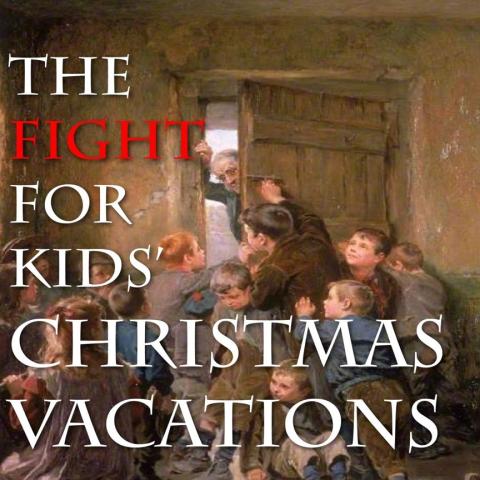

Today we take it for granted that a few days before Christmas, school children will be dismissed from class, and not return until after New Year’s. However, we owe these vacations to the bravery of students in centuries past. In many Protestant countries, Christmas Day was barely observed, and school masters expected children to go to school each day during this period. But kids—being kids—wanted time off. To get it, they engaged in a practice known as “barring-out the schoolmaster”. Students would plan a sit-in. It often began on St Nicholas Day, December 6th, so on the 5th, they would gather enough supplies to last for three days. Food, drink, blankets, even pistols (no joke)—everything they would need to occupy their classroom and keep their teacher locked out. This was a custom in Britain, the U.S., and some parts of Canada (an article in The Toronto Globe in December 1894 describes the practice at a school near Georgian Bay).

The rules were straightforward: use planks and nails to barricade the doors and windows shut. If the teacher couldn’t break in for three days, the school had to grant the students’ demands. Their typical request was for a week’s break from school at Christmas. Sometimes they asked for Christmas presents and treats instead, or along with time off. These demands could be denied—the door would be broken down and a sound thrashing was meted out on the students. Nicer teachers would negotiate a truce before the three days was up. This practice died out in the British Isles in the 18th century as schools adopted charters with vacation times set for Christmas. The practice continued all through the 19th century in parts of North America.

Progress often starts with people who are willing to go on strike, and Christmas vacation for students was no different. To paraphrase the Beastie Boys: You gotta fight for your right to Christmas vacation.

—Rev. Stephen Milton came to Lawrence Park Community Church in Toronto in 2019, after decades of work as a documentary filmmaker. His passion is creating new ways to explore spirituality, appealing to people who aren’t interested in regular Sunday morning church services.

The views contained within these blogs are personal and do not necessarily reflect those of The United Church of Canada.